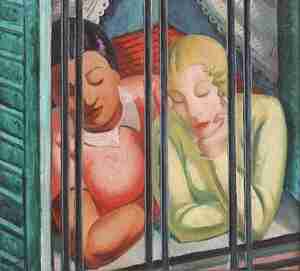

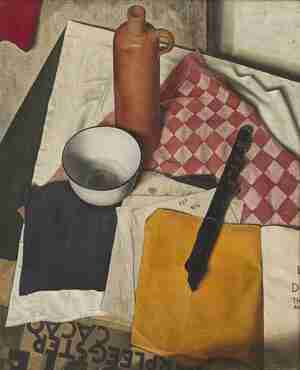

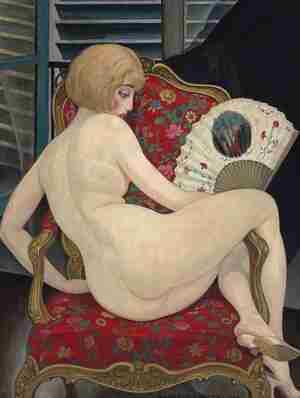

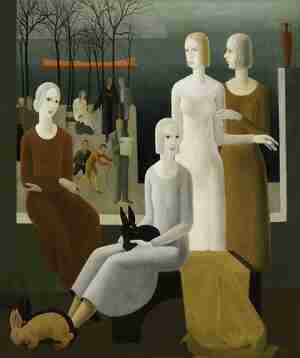

Exactly 100 years after the pioneering exhibition Die Neue Sachlichkeit (1925), this autumn Museum MORE will present nearly 80 neorealist highlights from 20 countries. This international exhibition is anything but a reprise; it offers a fresh perspective on European realism in the interwar years. In collaboration with Kunstsammlungen Chemnitz – Museum Gunzenhauser in Germany, Museum MORE will unite leading figures and rediscovered voices in the first exhibition of this scale ever held in the Netherlands. Featuring artists from Finland to Spain and from Hungary to England, among them Otto Dix, Meredith Frampton, Aleksandra Beļcova, Lotte Laserstein, Ángeles Santos Torroella and Gerda Wegener. Discover the rich spectrum of realist portraits, cityscapes and still lifes – painting between silence and storm.

The exhibition European Realities | Painting 1919-1939 is on display at Museum MORE in Gorssel from 11 October 2025 to 1 February 2026

A new Realism in a turbulent world

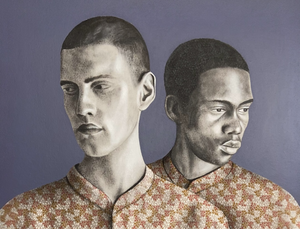

For many years, realism in the arts was considered old-fashioned, classical, or even reactionary. Yet the period between 1919 and 1939 tells a different story. Out of the turbulent interwar years, an innovative art emerged across Europe that radically broke with earlier (figurative) movements. Neorealists did not hark back to a nostalgic past, but sought instead to capture the here and now of their own time as clearly and faithfully as possible. Some artists also felt that the abstract visual language of the 1910s was unable to convey the horrors of World War I, the unsettling socio-political developments, a new view of humanity, and a more intimate inner world.

Pioneering

Seeking new forms of expression, artists from across Europe became acquainted with one another’s work, travelled to artistic hotspots such as Paris, Berlin and Rome, exchanged ideas, and brought them back home. The results of these cross-border dynamics reveal just how international and multifaceted the rediscovery of figuration truly was. With the diversity of their new realisms, these young artists formed the avant-garde of their generation.

Italy, France and Germany were the driving forces of this movement, which rose to prominence in the course of the 1920s and 1930s. The influence of movements such as Pittura Metafisica and Novecento Italiano extended far beyond Italy. Realist paintings could take on mysterious and disquieting qualities, and often focused on monumental subjects. In Paris, classicism flourished: the retour à l’ordre that sought peace and harmony after the war. In Germany, Gustav Friedrich Hartlaub’s pioneering exhibition Neue Sachlichkeit (1925) gave a name to a broad movement, ranging from sober, faithful painting to the biting social critique of Otto Dix and George Grosz.

A distinctive visual language

A wide array of new realisms also thrived beyond these hubs. In Great Britain, artists such as Meredith Frampton and William Roberts struck a fresh note, balancing photographic precision and social engagement. In Eastern Europe, countries pursued their own paths: Hungarian and Polish artists sought to connect with national traditions, while Latvia developed a ‘post-Expressionist realism’. In newly founded states such as Yugoslavia and Czechoslovakia, art also served as a means of shaping national identity. In the Netherlands, neorealism became the hallmark of artists including Pyke Koch, Carel Willink and Charley Toorop, who translated international influences into a visual language entirely their own. It is difficult to pinpoint an exact end date for this ‘new realism’. In Germany, a turning point came after 1933, when the Nazis branded such avant-garde art as ‘degenerate’. In the Netherlands and other countries, however, it continued to flourish until artistic production came to a halt with the outbreak of World War II.

Many voices

Earlier retrospectives often centred on Western European male artists. This perspective has since broadened considerably, with greater attention now given to Central and Eastern Europe, and to female artists. An exhibition like European Realities demonstrates just how rich, diverse and relevant this art is. It also makes clear that realism in the interwar period was never a single style, but a many-voiced movement that transcended borders. It calls for a broader view of art history – one attentive to differences, commonalities, and rediscovered voices.

Book

The exhibition is accompanied by a richly illustrated bilingual publication (Dutch/English), featuring an introduction by Anja Richter and Florence Thurmes, and an essay by Julia Dijkstra. Published by Waanders Uitgevers.

Artists

Robert Angerhofer, Aleksandra Beļcova, Giorgio de Chirico, Marcus Collin, Heinrich Maria Davringhausen, Fortunato Depero, Kate Diehn-Bitt, Otto Dix, Ferdinand Erfmann, Emanuel Famíra, Roberto Fernández Balbuena, Stina Forssell, Arvid Fougstedt, Meredith Frampton, Acke Hallgren, Krsto Hegedušić, Johan van Hell, Karl Hubbuch, Martin Hubrecht, Raoul Hynckes, August Jansen, Torsten Jovinge, Alexander Kanoldt, Dick Ket, Moïse Kisling, Vilma Kiss, Pyke Koch, Béla Kontuly, Sonja Kovačić-Tajčević, Tone Kralj, Lisa Elisabeth Krugell, Kazimierz Kwiatkowski, Lotte Laserstein, Chris Lebeau, Ludolfs Liberts, Jānis Liepiņš, Rafał Malczewski, Jenő Medveczky, Johan Mekkink, Omer Mujadžić, Martin Nagy, Ernst Nepo, Václav Vojtěch Novák, Väinö Nuuttila, Eduard Ole, Lotte B. Prechner, William Roberts, Cagnaccio di San Pietro, Ángeles Santos Torroella, Johannes Lodewijk Schrikkel, Georg Schrimpf, Franz Sedlacek, Ester Šimerová-Martinčeková, Ludomir Sleńdziński, Leonore Maria Stenbock-Fermor, Niklaus Stoecklin, Charley Toorop, Marijan Trepše, Ante Trstenjak, Kiril Tsonev, Remedios Varo Uranga, Karl Völker, Vlasta Vostřebalová-Fischerová, Ilmari Vuori, Gerda Wegener, Carel Willink.

Countries

Austria, Bulgaria, Croatia, the Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Great Britain, Hungary, Italy, Latvia, the Netherlands, Poland, Slovakia, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden and Switzerland.